Robert Burgoyne

Expressed only in its final scenes, DUNKIRK's culminating assertion of war as collective heroic enterprise and vehicle of national renewal might be seen as the belated return of genre memory, the restitution of a familiar theme just before the final curtain. In these closing moments, the young soldier-protagonist and his friend, newly rescued from the waters off Dunkirk, are portrayed riding on a train to face what they fear will be almost certain social death. Their desperate retreat from France, absent a shred of military success, will surely be met by folks "spitting at them in the streets." Pulling into a station, one of the young soldiers asks for a newspaper, and begins reading aloud Churchill's famous address to the people of Britain, the rousing "We shall fight on the beaches" oration. A series of cross cuts follows, indexing the three main story-lines of the film -- from the cheering reception the returning soldiers receive in the station, to the beaches of Dunkirk where the RAF pilot has just landed his Spitfire and incinerated it so it would not fall into enemy hands, to the Weymouth home, where the captain of the small boat that had been part of the rescue operation looks searchingly at his son, as they share the local newspaper with its lead story about their shipmate, "George," who has died during the passage.

In this closing sequence, the signs and symbols of an imagined community beaten into shape by the hammer of war are profusely arrayed. Churchill's address, spoken aloud by the everyman soldier-protagonist reading the newspaper, evokes the seas and oceans, the air and the beaches, the fields, streets, and the distant colonies that the people of Britain will defend, "wherever the fight may be." The oration poetically enumerates the very places where national feelings coalesce, where the mythology of nation takes form, the ancestral groves and the mystic seascape. The daily newspaper is also foregrounded. As Benedict Anderson has famously described it, the daily newspaper is the very emblem of the imagined community, forging a sense of simultaneity and parallelism among a scattered population, linking together, in daily summary, a disparate people moving together into history (1). As if to underline the point, the cross cut sequence also includes a map on the lap of the pilot, a large clock in the boat captain's home, and a second, local newspaper featuring the story of young George's sacrifice. And in the figure of cross cutting itself, a primary formal device in the film, time seems finally to have been synchronised, with the three temporal schemes of the work each coming to conclusion, more or less, in dramatic accord.

(1) Anderson, Benedict: Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London / New York 2016.

I. The Beaches

In the main body of the film, however, DUNKIRK presents a very different world -- a world that has been stripped to an existential minimum, with none of the performative gestures of national belonging or the rituals of military life. Stranded on the beach, the soldiers confront not the enemy but the void, a wasteland, where the threat of extinction seems to come as much from despair as from the German Luftwaffe. Moreover, in these scenes, the generic markings of war cinema have mostly been erased, as the mise en scène of war -- the military machinery, the well-ordered task performance, and the mass movement of soldiers and equipment is starkly reduced. The film, instead, unfolds in repeated shots of soldiers staring out to sea, etched as black figures against an empty horizon. No campsites or tents can be seen, nor any kind of bunker. Coupled with an absence of dialogue and the constant sound of the sea, the portrait of war that the film presents is permeated by anxiety and existential dread, as far removed from the collectivity of the imagined nation, so powerfully evoked at the end, as possible.

Samuel Hynes, emphasizing the particular strangeness of combat experience in various settings, has coined the term "the Battlefield Gothic" to describe the uncanny transformation of space and geography that distinguishes war, a strangeness that cannot be fully communicated or described (2). For him, the conventions of realism, which seems to be the default code of war literature and war cinema, are simply not adequate to the grotesque visions of the battlefield that soldiers confront in the numerous memoires he studies, ranging from the trench warfare of WWI, to the jungles of Vietnam, to the horrors of the Holocaust and Hiroshima. As Hynes describes it, the Battlefield Gothic is a form and style of expression that recurs in soldier memoires, as they attempt to capture the grisly experience of death and wounding that characterizes combat. Although he does not extend his analysis to films, the memoire form he discusses seems to me to have much in common with the genres of Expressionism and Horror, in which extreme experience exceeds the representational codes available to express it.

(2) Hynes Samuel: The Soldiers’ Tale. Bearing Witness to Modern War. New York 1997.

In the film DUNKIRK, however, the Battlefield Gothic takes a very different form. Rather than gruesome display -- the fascinating and macabre forms of mortal wounding conveyed in the opening scene of SAVING PRIVATE RYAN, for example, or the grotesque tableaus that dominate Kurtz's compound in the closing scenes of APOCALYPSE NOW -- the most striking and lasting impression left by DUNKIRK is the uncanny feeling of desolation it conveys. The existential fear at the heart of war hovers over the scenes on the beach, a theme expressed in group shots of men standing, silently, not looking at one another, not speaking, and in shots of individual figures portrayed often in full length images.

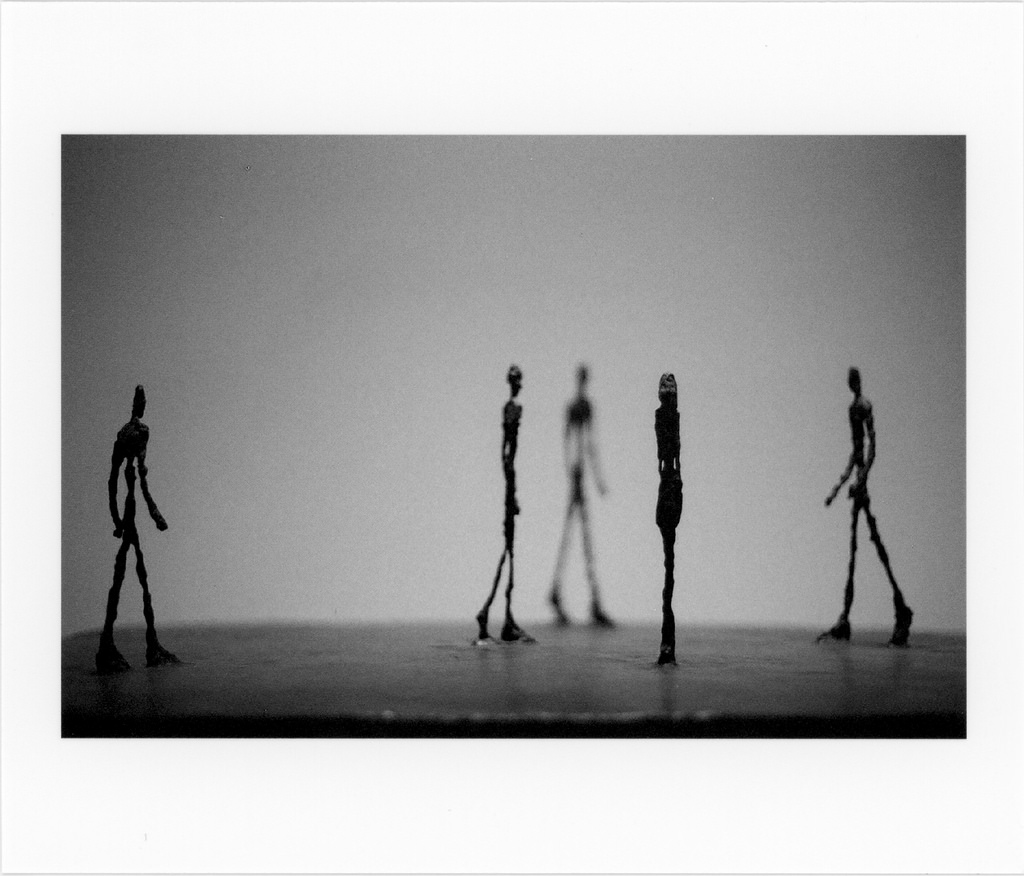

The first time I viewed the film, I was struck by the sense of existential emptiness that seems to characterize the visual patterning, particularly in the scenes on the beach. I found the striking visual style -- the preponderance of full body shots, the absence of movement within the frame, the void that seems to exist around the figures -- to be reminiscent of the sculptures of Alberto Giacometti, with his elongated, dark figures situated in a space evacuated of all objects or decor.

Clip 1: DUNKIRK (Christopher Nolan, UK/USA/F/NL 2017), Min. 49:44 - 52:21.

In the film, numerous, long duration shots of men standing or sitting on the beach, and the scene where a lone man walks directly into the sea, reminded me of the famous Giacometti sculptures The Piazza, or Three Men Standing, or, his most celebrated work, Walking Man.

Although the links I see between DUNKIRK and certain examples of postwar Modernist art are certainly too tenuous to be called an influence, I do feel they reveal an aesthetic affinity, one that underlines a tone in the film that in many ways cuts against Christopher Nolan's own insistence, in numerous interviews, on the film's theme -- the struggle for individual survival transformed into a collective victory and renewal of national will. With its motifs of solitude, alienation and loss, the beach scenes of DUNKIRK depict a horizon "stripped bare of the social," (3) recalling the existential modernism of the postwar period, a style and a mood that I feel inheres in the film's visual and acoustic style.

(3) Eagle, Joanna: Letter to the author. 2019.

The overall visual style of the beach scenes, for example, is defined by the isolation of soldiers in medium long shot, and also, importantly, by stasis. Dynamic movement is almost entirely missing here. The soldiers are fixed in their places, standing in near frozen postures, or sitting silently in the foam and sand. The camera movement, likewise, is dramatically slowed down, with no fast or medium speed tracks or pans. And the pace of the editing is deliberate, almost bradycardic.

The static visual design of the beach scenes, relieved only by crosscutting to aerial shots or to scenes of ships sinking in the night, or to the little rescue boat making its way slowly across the Channel, gives the work a very unusual rhythm, one that is entirely at odds with the ordinary depiction of World War II in the visual culture of war. One of the most characteristic motifs of World War II representation is the dynamic movement of armadas of ships, squadrons of planes, large formations of tanks, and massive assaults by mobile armies (Hynes 1997, 116-120). A sense of speed and momentum, of continuous movement from one battleground to another, from one country to another, characterizes the popular imagery surrounding this war. Unlike World War I, which was defined by trench warfare with its static lines of defense and its utter absence of progress or change, World War II has been visually imagined in terms of sweeping, large scale movements of heavy machinery and groups of men.

In contrast, the visual style of DUNKIRK, with its numerous near-frozen tableaux, underlines the existential as well as the physical sense of entrapment. Attempts to leave the beaches, whether in rowboats, or in a Red Cross hospital boat, or in an abandoned trawler, are futile. Time and again we see boats sinking just beyond the beach, or being bombed at the Mole, the large breakwater that extends out to sea. It is as if the beaches of Dunkirk had a magnetic force field around them; the soldiers who attempt to leave are either drowned or must swim back to drag themselves up onto the sand. And as one character says, you can tell when the tide is coming in, as that's when the bodies come back.

II. The Boat

In the midst of the bleakness of the beach, the arrival of the flotilla of little ships that will begin to convey the soldiers across the Channel creates a crescendo of positive emotion. The enthusiasm that greets this first wave of civilian rescue craft stands out in the film for its exuberance and sheer joy. Against this single scene of euphoria spliced into the body of the work, however, DUNKIRK provides a dark counterpoint in the figure of a traumatized soldier, rescued at sea by the small boat, the Moonstone, who violently objects to returning to the beach to rescue soldiers still stranded there. A threatening figure, the traumatized soldier commands our immediate recognition: in a largely bloodless narrative, the injury and pathology of war is largely concentrated in this haunted figure whose momentary violence results in the death of the young boy, George.

Quite early in the film, the Moonstone encounters the lone soldier sitting on the sinking stern of a large ship, the sole survivor of a U-boat attack. Almost reluctantly, it seems, he allows himself to be rescued, and, huddling on the deck of the rescue boat, appears to withdraw deep into himself. Brooding, possessed by fear, the character gives the impression of having looked into the abyss. As the pilot of the boat says to George, the man has suffered shell shock, and may never be himself again. When he discovers that their destination is Dunkirk, however, he snaps to awareness and refuses to go back, ultimately struggling with the pilot of the boat for control of the wheel, and accidentally pitching the young boy George off him, who falls down the stairs and slams his head against a piece of machinery.

Clip 2: The Face of Trauma. DUNKIRK (Christopher Nolan, UK/USA/F/NL 2017), Min. 32:57 - 35:17.

Clip 3: The Face of Nation. DUNKIRK (Christopher Nolan, UK/USA/F/NL 2017), Min. 45:35 - 46:14.

The initial confrontation is staged directly in front of the ship's flag, a composition that sets the face of trauma immediately against the Union Jack, condensing in one shot two competing signs and narratives of war. The staging of the scene makes the symbolic stakes of the confrontation explicit. Seen in close up, the face of the traumatized soldier embodies the authority of the "flesh witness," one who has experienced war not simply as an eyewitness, but with his own flesh. The boat's pilot, for his part, filmed from a slightly low angle, conveys a competing discourse of authority. With the nation's flag behind him and later, in front of him, he describes the rescue mission in terms of a compact binding the generations together, a covenant between the old who are making the decisions and the young who are being sent to die, giving voice to the idea of war as what Hermann Kappelhoff calls "the front line of community" (4).

(4) Kappelhoff, Hermann: Front Lines of Community: Hollywood Between War and Democracy. Amsterdam 2018. (Translated by Daniel Hendrickson)

Kappelhoff has written extensively about the image of the shell-shocked soldier in film and photography. Generally rendered in close up, the young soldier, paralyzed by fear -- suddenly aware of the imminence of death -- serves as an emotional icon of war's cost. For Kappelhoff, the response aroused in the spectator by these types of images, a response of outrage and revulsion at the needless sacrifice of the young, creates a sense of collective anger and horror in the audience – an emotional response that is then recuperated in the war film by formulas designed to convert pathos to national feeling, mapping the pathos associated with trauma onto larger themes of collective purpose and the necessity of sacrifice (Kappelhoff 2012, 43–57).

This convention, however, appears to be undermined in DUNKIRK. The traumatized soldier refuses to become a vehicle for pathos, and turns away any attempt at an emotional or empathetic identification. He serves, instead, as a figure of rupture, embodying the breakdown of the social covenant, belligerently rejecting any notion of death in war as necessary sacrifice. It is as if he has brought the existential gloom of the beach onto the boat.

A very different reading of trauma in war from that offered by Kappelhoff is given in the work of the historian Yuval Noah Harari. The victim of war trauma, Harari writes, brings into sharp relief a conception of war that has framed Western understanding for the past two centuries -- the idea of war as truth, as revelation (5). "Western culture still attaches one supremely positive value to war. Deep within late Modern culture, the relation between war and truth is hammered again and again. The master narratives of late modern war all agree that war reveals eternal truths -- even if weakness prevents people from facing them" (Harari 2008, 305).

(5) Harari, Yuval Noah: The Ultimate Experience: Battlefield Revelations and the Making of Modern War Culture, 1450-2000. London 2008.

The idea of war as revelation is paramount in Harari's reading, a theme that is crystallized in the image of the traumatized soldier -- one who has seen the truth of war, and the truth of the self. As Harari writes, "The story of PTSD is frequently narrated as a story of negative revelation, in which the horrible truths exposed by war transform the innocent 'boy next door' into a war criminal, a social misfit, or a madman" (Harari 2008, 4). Although the traumatized soldier may be lost to society, he is never understood to be in error, or to have witnessed an illusion. He has experienced the truth of war with his own flesh. He is a "flesh witness," rather than a mere eyewitness, one who has "looked behind the curtain of ignorance." In Harari, the traumatized soldier serves as the antithesis of the idea of the imagined community catalyzed into being by war, a man who has seen "too much of the truth for his own good, and is shunned ... by a society unable to stomach that truth" (Harari 2008, 4).

III. Conclusion

DUNKIRK sets forth two incommensurable narratives of modern war, alternating between a vision of war as collective historical emergence, the realization of a deeply ingrained national character, and, contrarily, a sense of war as utter desolation, loneliness, and waste -- dual narratives that have, at different times, permeated the wider Western understanding of war. From one perspective, the film appears to imagine war as the "frontline of community," as Kappelhoff has called it, evoking a shared public meaning that gives rise to "feelings of commonality." In keeping with this, the distinctions between soldiers and civilians are set aside in DUNKIRK, and class differences disappear, giving particular expression to the British myth that World War II had transformed "class-ridden England" into a classless society (Hynes 1997, 129). The film portrays Britain rediscovering its common, mystic nationhood under the threat of almost certain annihilation.

Viewed from another perspective, however, the film conveys a very different theme -- of war as existential drama in which all the flourishes and trappings of nation are dissolved. In this scenario, war, and especially war's violence, is stripped of its generative associations, offering instead a stark external and internal landscape of emptiness and vulnerability. The dark, static figures of soldiers on the beach, and the brooding isolation of the traumatized soldier on the boat, manifest a sense of war that is empty of meaning, a void, without symbolic value.

In highlighting these two recurring paradigms of modern war in DUNKIRK, I have bracketed out the film's drama of aerial combat, with its spectacular pilot's eye view. In this narrative strand, combat takes the form of individual performance in which machines battle machines, paradoxically providing the space and the opportunity for heroic agency in war. The aerial combat narrative in DUNKIRK, however, seems to me to be a plot inherited from the First World War with its aces and its Red Barons, already mythologized at the time of the film's reference period. Indeed, the film times the cutaways to aerial performance just at the points when the beach and boat narratives seem most grim, as if to provide a few moments of what Tanine Alison has called the "destructive sublime" (6).

(6) Alison, Tanine: Destructive Sublime: World War II in American Film and Media. New Brunswick 2018.

What I have emphasized, instead, is the undertow of the rescue narrative, the scenes that speak to a sense of helplessness and dread. Hynes writes that the immobile trench warfare of WW I is "a paradigm of modern war as we conceive it, or feel it: war as total unwilled destruction, with neither advantage nor victory, only annihilation of men" (Hynes 1997, 75). The stasis of the beach scenes in DUNKIRK strikes a similar chord for me, suggesting a different narrative of war lying beneath the film's surface chronological patterning.

Paul Ricoeur has written of narrative form as defined by two patterns of time and event, episodic and configurational (7). As a genre, the war film typically unfolds as an episodic recounting, centered on a linear succession of historical or dramatic events (Ricoeur 1980, 178). DUNKIRK, however, allows us to glimpse a narrative of war that is something other than an episodic set of events or a mere "succession of instants."

(7) Ricoeur, Paul: Narrative Time. In: Critical Inquiry 7/1 (1980), 169-190.

With its sequences of perpetual waiting, its suspension of time on the beach, and its glimpse into the void suggested by the haunted soldier, a very different approach to the war narrative emerges, in which war is construed as a constant state, without beginning or end, and where the wars of the past begin to merge with the wars of the present and the future.

Bibliography

Alison, Tanine: Destructive Sublime: World War II in American Film and Media. New Brunswick 2018.

Anderson, Benedict: Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London / New York 2016.

Eagle, Joanna: Letter to the author. 2019.

Elsaesser, Thomas: Saving Private Ryan: Restrospection, Survivor's Guilt and Affective Memory. In German: Retrospektion, Überlebensschuld und affektives Gedächtnis: Saving Private Ryan. In: Thomas Elsaesser / Michael Wedel (eds.): Körper, Tod und Technik. Metamorphosen Des Kriegsfilms Paderborn 2016, 65-102. (English translation supplied by the author.)

Harari, Yuval Noah: The Ultimate Experience: Battlefield Revelations and the Making of Modern War Culture, 1450-2000. London 2008.

Hynes Samuel: The Soldiers’ Tale. Bearing Witness to Modern War. New York 1997.

Kappelhoff, Hermann: Front Lines of Community: Hollywood Between War and Democracy. Amsterdam 2018. (Translated by Daniel Hendrickson)

Ricoeur, Paul: Narrative Time. In: Critical Inquiry 7/1 (1980), 169-190.

Filmography

APOCALYPSE NOW. Francis Ford Coppola, USA 1979.

DUNKIRK. Christopher Nolan, UK/USA/F/NL 2017.

SAVING PRIVATE RYAN. Steven Spielberg, USA 1998.