Some of us call them “images”, some of us believe they are just casual formal similarities, some of us, like Le Corbusier, with subliminal intuition, collected them under the name of “Objects of poetic reaction”, a very appropriated name.

Le Corbusier selected these objects for their potential to become sources in a yet not initiated, cross-domain transference of attributes from made things to things yet to be made, a collection of architectural riddles.

1. If Pictures have no movable parts and no hinges, it follows that we would have to do without them on our windows.

Consequently we modified our ventilation system, the ventilation was performed no more by the windows but by skylights and windows in secondary rooms connected to the reading hall, in this way we avoided the necessity to open the windows and did without hinges and openers.

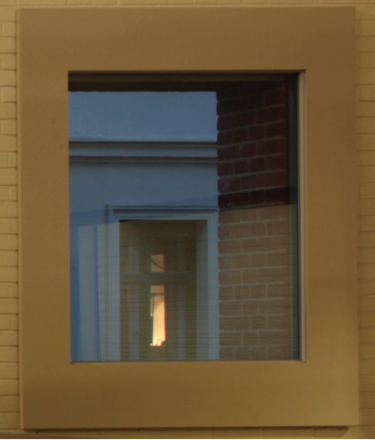

2. If a window is a picture, then it has to hang on the wall and not be inserted in it.

To avoid what we call “cold bridges” (another nice metaphor for you there), meaning missing places on the continuity of the insulation that allow energy to flow between inside and outside, we have to place thermal insulation around the window, we did it in such a form that a frame was needed to cover it, a frame “on the wall”.

This was a way of hanging pictures on the Eremitage Museum in San Petersburg – also known as salon-style hang – and actually not related to our looking for a disposition of our windows in our reading hall, but our debate was already contaminated by the equation WINDOW=PICTURE, and “inferences” were emerging without being asked.