Carmen Hannibal

I. Introduction

It is surprising to discover that there are only a few writings that, in various levels of detail, engage with the topic: how animation and metaphor influence and interact with each other (Leyda [ed.] 1986; Wells 1998; Honess Roe 2013; Forceville 2008, 2007a, 2007b, 2007c, 2011; Forceville / Urios-Aparisi [ed.] 2009). The term (visual) metaphor is, nevertheless, often used to ascribe meaning within the animated film, both by animation practitioners about their productions (Svankmajer 1997; Tan 2011; Reckart 2013; Lucander 2014; Firth 2014; Vázquez / Rivero 2016, just to name a few) and animation scholars accounting for the animations (Wells 2002; Wu 2009; Moore 2011; Fore 2011; Cavallaro 2012; Pilling [ed.] 1997, 2012, among others). This suggests that there may be an inconsistency between the academic findings on metaphor in the animated film, and the discourse used to talk about the content that is dealt with within this format.

The aim of this paper is to shed light on how metaphor can be contextualised within the animated film, exemplified through the representation of subjective perspective. This will be done by making use of theory in animated documentary to discuss the representation of subjectivity in the animated film, in combination with Conceptual Metaphor Theory to discuss the idea of understanding concepts “in terms of another” (Lakoff / Johnson 1980: 5). The choice to investigate the animated film and not other modes of animation is primarily motivated by current research on this particular format, both in academic animation studies and in cognitive metaphor studies. Hence this paper will depart from these findings and debate. Two case studies will be used to exemplify how metaphor for subjective perspective in the animated film can work in the continuum of spoken conventional metaphor onto creative multimodal metaphors. Most attention will, however, be given to the analysis of American animation director Chris Landreth’s computer-generated short film RYAN (2004), due to its innovative exploration of subconscious expression through metaphorical effects. Following this, it is the goal to outline the findings on how multimodal metaphor is facilitated by the animated film. Brief suggestions will finally be given to encourage possible directions for further research in the area of metaphor in the animated film.

II. Representing Subjectivity

One of the areas in academic animation studies that have discussed how subjective perspective is expressed through metaphorical effect in the animated film is research within its subgenre, ‘animated documentary’. Documentaries are in a traditional sense often characterised to depict factual aspects of human condition, social, institutional and political issues (Kuhn / Westwell 2012). Film theorist Bill Nichols asserts this in a simple and effective manner when he describes how documentaries are mainly concerned with “the world in which we live rather than a world imagined by the filmmaker” (Nichols 2001: 13). Such notion of the documentary also embedded a long-standing expectation that the nonfictional events are reflected in objective and mimetic representations. A belief that somewhat seems to exclude more abstract and subjective forms of expression often associated with the construction and manipulation of created worlds in fiction. However, the increasing use of animation within documentaries in recent years has started to challenge this traditional assumption about representation, because animation by nature requires almost everything to be created, and this intervention has been claimed to make animation incapable of representing 'the real' (Ward 2006: chapter 5).

Supported by previous attacks on the possibility of complete objectivity in the traditional documentary when representing the world, animation scholars have been able to argue that more personal and non-mimetic forms of expressions known from a world of animation have taken shape within documentaries. Especially when it comes to representing abstract matters of the mind, such as internal worlds and conscious experiences. The problem of documenting and representing such phenomena, which do not have a visual equivalence and are not accessible to the traditional film camera seems clear, and animation has proven to be advantageous in terms of representing these fundamental aspects of 'the real', namely that we seem to live in a shared factual physical world, but we simultaneously experience this world differently from person to person. These subjective experiences can be represented in animation, and this is in practice demonstrated by the way that animation in documentary can continually maintain an indexical bond to the factuality of the event through audio recordings (the world), and then combine this material with partly or complete animated imagery (a world), in order to creatively represent and interpret what which is, or is not, heard in the audio track. Such representation of events provides the viewer with an alternative treatment and knowledge-creation about the subject matter compared to more matter-of-fact approaches, which in best cases helps our understanding of the world (Honess Roe 2013: chapter 4).

Professor in animation studies Paul Wells uses the term 'narrative strategies' in animation to discuss how the presentation of a storytelling event "(…) finds unique purchase and execution in the animated form” (Wells 1998: 68). Even though there are some shared narrative strategies that can be employed both in live action film and the animated film, animation has some unique medium-specific properties, which enables very distinctive ways for the filmmaker to represent the events that communicate the content of the story. According to Wells, the main feature of metaphor as one of these narrative strategies is its ability to establish meaning that runs parallel to the storyline. This makes it possible for a metaphor to be interpreted through its symbols, but at the same time remain open for more than one discourse within the story. Different to symbols, as Wells points out, metaphors are therefore not necessarily related to the evident imagery, but instead metaphors create a framework, where the meaning derives from an understanding of the symbols, but not automatically in a one-to-one relation (Wells 1998: 84). Wells description does however not go into details about how metaphorical meaning is created from the second-order notions of representations, as it remains a broad understanding of metaphor.

III. Visual and Multimodal Metaphor

Cognitive linguist George Lakoff and philosopher Mark Johnson's asserted in relation to their Conceptual Metaphor Theory that "the essences of metaphor is understanding and experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another” (Lakoff / Johnson 1980: 5). Their theory suggests in brief, that humans not only use metaphor in language but fundamentally think metaphorically when abstract phenomena (target domain) are being transferred into something concrete (source domain) based on our embodied experience with the surrounding world and in a systematic and structured manner. Conceptual metaphors do therefore not work in any random fashion, and this distinction is important to be aware of, if one is not to confuse Lakoff and Johnson's definition of metaphor with an understanding that, everything that can be replaced 'with something else' therefore has metaphorical meaning.

When it comes to conceptual metaphor in animation one is more specifically referring to visual and multimodal metaphor, as Donald Crafton points out, the 'animated effect' only exists due to our biomechanical basis for seeing successions of images as complex cognitive frameworks (Crafton 2011: 96). There have been numerous methods proposed for recognising and categorising visual metaphors, however, due to the scope of this paper the focus will be on cognitive metaphor scholar Marianna Bolognesi's annotation scheme for visual metaphors and Charles Forceville's notions for multimodal metaphors, and only relevant aspects of their models will be accounted for and employed in terms of the case studies. There are some general observations from their studies that will inform this paper. Bolognesi stresses that it is difficult to articulate an A-is-B format for visual metaphors. This is due to various reasons, and the first concern is the issue of determining at what level the metaphor is expressed. This challenge is a matter of picking out the features of the visual metaphor that is part of the definition of the metaphor itself, such as depictions, context and level of abstraction for the domains (Bolognesi 2014: VisMet annotation scheme).

It is thus important to be aware that a coherent identification of 'visual metaphors' is still developing due to the many variables that need to be considered and due to the fact that the recognition of the pointers is of a different kind than in language. With few refinements to Forceville’s research on metaphor in advertising (Forceville 1996: 162–164), Bolognesi affirms that visual metaphor can occur in primarily three various contextual structures for its visual level of expression, namely 1) fusion; where target and source domains are depicted at the same time in a unified image, 2) replacement; where either the target or source domain is depicted, and the other is only cued via the context, and 3) juxtaposition; where the target and source domains are depicted alongside each other. According to Bolognesi, it is furthermore possible for more than one structure of visual metaphor to appear within a framework, and in such instance, the leading metaphor will be the one that is most dominant.

Metaphors in moving images are furthermore complicated due to the mediums specific properties of the film, which in most cases today make use of other means than pure visuals to express its content, such sounds, editing / cinematic time, text, colour, speech and gesture. Forceville's work on 'multimodal metaphors' has shown that these metaphor have additional means than visuals to representing and defining the target and source domains of a metaphor. In short, Forceville accounts for nine various 'modes' (Forceville 2009: 23) in which the combination of at least two different modes can provide the metaphorical effect. This enables metaphors in the animated film not only to be visual but also to be multimodal, as the target domain and the source domain can potentially be cued from different modes of communication.

The film medium also often stretches over an extended time span, where the individual shots, scenes and sequences in combination create the (narrative) structure and meaning of the work. Visual metaphor in a film can, for this reason, be sequential because the metaphor can appear over time. Forceville describes how the target and source domain now can be displayed one after another and not necessarily having to be depicted simultaneously in one single image as traditional pictorial metaphors require. This enhances the notion that a clear A-is-B format is hard to distinguish in film metaphors, and that the metaphor in a film is not always possible to detect in single shots, scenes or sequences, but may be distributed over several instances. He further points out that, metaphor in film sometimes develops gradually over time as the film progresses, and one will often need to be cautious about how the relationship between the target and source domains are constructed and interpreted in the duration of the film in order to observe potential metaphorical meaning. The time aspect can likewise increase the possibility for metaphors in the animated film because its cinematographic properties can be used to exploit metaphorical meaning.

The medium of animation has a few additional elements, which divert from film, and those medium-specific properties likewise complicate the detection of metaphor. Forceville explains that animation does not have a profilmic reality and the interventions of creating the material do in some cases lead to animations that do not contain much dialogue, are not restricted to gravity and physical laws, contain visual exaggerating or simplification, allow metamorphosis and reveal visual penetration. These differences from the film make metaphor in animated film provide good opportunities to support the Conceptual Metaphor Theory (Lakoff / Johnson 1980), and points to the matter that creation and the perception of metaphor are also informed by the medium in which it is presented (Forceville 2011).

IV. Case Studies in Metaphorical Connotations

According to Bolognesi and Forceville, its seems that conceptual metaphors in the animated film is different to linguistic, and even slightly to visual and film metaphors. They must, therefore, be analysed and understood on their own terms with regards to their differences ranging from contextual styles to medium specificities, which all together inform whether or not one is able to subtract metaphorical meaning. It is the goal in the following text to outline the author's analysis of how metaphor in the animated film can work in the continuum of visualising a spoken conventional metaphor, onto facilitating a creative multimodal metaphor that conceptualises subjective perspective. It is important to mention that the two case studies are two of the opposite scale of the continuum and that these examples are not enough to generalise about metaphor in the animated film. It is, however, the hope that the two studies may spark an interest in looking closer at all possible variations of metaphor in animated film that could lie in between or beyond the examples given.

IV.a. ROCKS IN MY POCKETS (2014)

The first case study is from Latvian animation director Signe Baumane's mixed media feature animation film ROCKS IN MY POCKET from 2014. The animated film is partly a self-biographical piece, where Baumane herself narrates various stories of mentally unstable women in her family history that eventually connects to her own experience of having schizophrenia. For the purpose of this paper, the focus will be on how Signe Baumane represents the intelligence of her grandmother, as this example showcases a more conventional approach to the usage of metaphor in animated films.

The clip consists of the voiceover of Baumane who is describing her grandmother, Anna, as a young girl. Starting with a long shot of Anna in a blue dress with long braids, she is sitting with an unspecified book at a desk in an animation set which is a fairly dark lighted room. It cuts to a slightly low angle so that it is possible to see how her eyes quickly move across the page. Cutting to a slightly high angle medium to long shot of her, and as Baumane is pronouncing her verbal metaphor 'she was the brightest student of them all' (ROCKS IN MY POCKET, Signe Baumane, LAT 2014, Min. 03:17–03:26), Anna's head becomes larger and then turns into a light bulb in the animation technique and narrative strategy of 'metamorphosis' (Wells 1998: 69). This frame stays onscreen for a short while until it cuts back to a long shot of her, and the light bulb for her head has returned to Anna's normal face (Clip 1).

Clip 1: ROCKS IN MY POCKET (Signe Baumane, LAT 2014), Min. 3:17–3:26.

Taking into account Marianna Bolognesi and Charles Forceville's research into visual and multimodal metaphor, the example above is a metaphor that has been conveyed both as a spoken and visual metaphor. This observation is important to point out as this makes the metaphor monomodal, even thought it might first appear as a multimodal metaphor. Forceville stresses that multimodal metaphors require that either the target or source domain is cued by two or more different modes, and the metaphor will lose its meaning if one of the cues are removed (Forceville 2007a). In this case, the metaphor 'she was the brightest student of then all' is pronounced just before the imagery repeats the metaphor visually, and the metaphorical meaning has in that sense already been revealed, making the animation supplementary, however, not essential for the metaphorical meaning-making.

In the spoken metaphor the target domain is the intelligence of Baumane's grandmother and the source domain is a light source, and this phrase contains metaphorical meaning as the intention is to map a light source onto Anna's character of being intelligent. The metaphor 'she is bright' derives from Lakoff and Johnson's examples of conceptual metaphor under the heading UNDERSTANDING IS SEEING (Lakoff / Johnson 1980: 48), which has the sub-mapping of INTELLIGENCE IS A LIGHT-SOURCE (Sullivan 2013: 41–43). The metaphor in Bauman's animated film is thus a spoken metaphor, which according to Lakoff and Johnson's Conceptual Metaphor Theory is presented in human's cognitive structure of the everyday concept, of 'being intelligent' understood metaphorically by our experience of 'light' (sources). The idea of providing an image to a spoken metaphor in the animated film has often the effect of emphasising the subjects experience in terms of a metaphorical description of it (Horness Roe 2013: 119).

This way of visualising spoken metaphor in the animated film does however often have its limitations for creative interpretation as the animated metaphor fairly directly visualises the spoken metaphor and its described elements. The animated imagery simply depicts the relevant properties of the metaphor, and does in those instances not challenge the viewer's need for ambiguity, but reiterates the conventional metaphorical understanding through the cross-domain mapping between 'intelligence' and 'light'. The target and source domain are in the animated version of the spoken metaphor 'fused' together over time into one single visual entity, creating an echoing effect between the audio and the visuals, where the target domain is first presented in the depiction of the grandmother and then the source domain becomes visible from the metamorphosis of Anna's head into a light bulb (Fig. 1–3).

Such use of metaphor in the animated film could be argued not to be bringing much depth to the conceptual meaning and treatment of the subject matter, which is not already expressed in the voiceover by Baumane. The described type of metaphor in the animated film can at best provide a visual clarity to the audience regarding the linguistic or spoken metaphors one is already familiar with, but may not contribute to significant new information and demand for metaphorical interpretation.

IV.b. RYAN (2004)

The second case study is from American animation director Chris Landreth's computer-generated short film RYAN from 2004 (Canada). The animated short film is a partly animated documentary about Canadian animator Ryan Larkin's (1943–2007) story from being a creative genius to developing a use of strong alcohol addiction, and Landreth's own fear of suffering a similar destiny. The soundtrack is the dialogue between Larkin and Landreth during the interview(s), Landreth's conversation with the additional subjects that appears in scenes of flashbacks, as well as Landreth's voiceover, which leads the narrative. The animated documentary takes place in the homeless mission that Larkin is staying at, and they are sitting at a table in the dinner room talking about Larkin's success and later troubles. For the purpose of this paper, the focus will be on how Landreth represents the subjective experience of his 'dread of personal failure'. The metaphor in this animation is articulated in the first scene and further developed over three other scenes. The opening scene will be described below as this animation neatly constructs the premise of the documentary and informs its metaphorical interpretation, and the other scenes will be highlighted for their relevance for the overall case study of this paper.

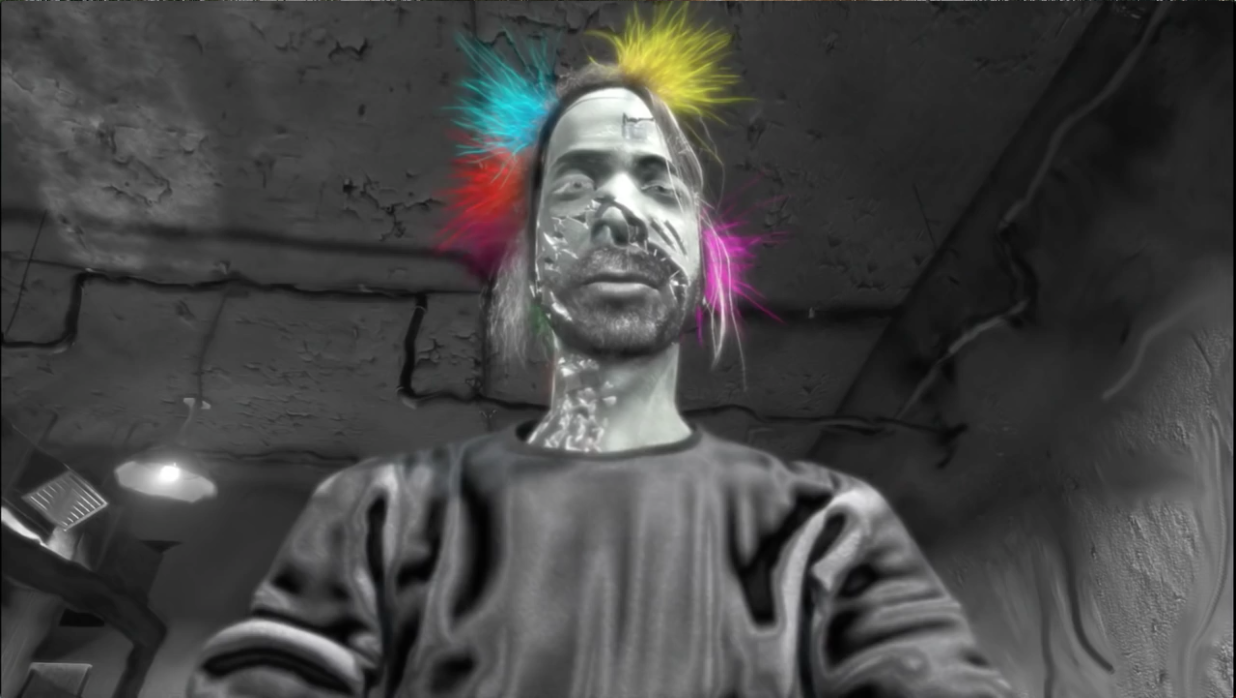

The animated short film starts with a long to medium short of a computer-generated version of Chris Landreth, standing with his armed crossed in a rough looking communal restroom near the porcelain sinks facing the simulated camera as he states his name and purpose; "(...) to explain some things" (RYAN 2014, Min. 00:23–00:27). The style is hyperreal, with detailed depictions of Landreth and the surroundings. He turns toward the nearby mirror, and in an over the shoulder shot Landreth continues to explain the deformations on his head, which have appeared in the cut from one shot to the other. The environment reflected in the mirror also moves noticeably. The camera zooms into a close-up of Landreth's head in the mirror, just before cutting to a high angle shot of Landreth in a black ambiguous space and the camera moving into the crater in Landreth's head that consists of a bright yellow smiley face and a bunch of sunflowers, accompaniment by a scream from a male and rattle sounds. Cutting back to Landreth in a medium shot and slightly fisheye lens, he looks directly into the camera from the angled reflection in the mirror and stresses that "but before all that, I took on a paralysing, self-defeating and all-pervading dread of personal failure, October 1963. Age two." (RYAN, Min. 00:51–01:02).

As he tells this on the audio with underwater bubble sound, the image turns monochrome and in a timely manner the editing emphasises each pronounced adjective with cuts from a medium to a low angle close up shot of Landreth's face. For the statement "(…) personal failure" (RYAN, Min. 00:57–00:59), the camera returns to a low angle medium shot as bright multi-coloured strings appear from behind his head and wrap around his head in a fast and snappy movement with wiping-squishy sounds with continued underwater bubble sound effects, making Landreth's head and body move slightly from the impact. It cuts to a long shot of a black and white photo of Landreth as a young child, bright multi-coloured strings similar to the previous ones wrap around the child's head, resulting in the child crying. Cutting back to Landreth in a medium shot, he is rendered back to his complete self, leaning over the porcelain sink looking into the mirror, where the reflected environment is moving. He redirects his explanation; "But I'm getting off the subject here, I am afraid." (RYAN, Min. 01:03–01:06). In a cut that flips the image 180 degrees horizontal, Landreth is again depicted with his visible deformations and the environment is heavily distorted, he further utters; "This story is about Ryan." (RYAN, Min. 01:07–01:09). The shot fades into a high angle shot from the centre of the restroom, where Landreth walks out of the screen as a vanishing figure before reaching the end and the sound of wind blowing starts to play on the audio, accompanied with western themed guitar music (RYAN, Min. 00:23–01:16) (Clip 2).

Clip 2: RYAN (Chris Landreth, CAN 2004), Min. 0:23–1:16.

The above scene illuminates several technical and conceptual properties of 3D animation, where the use of these features makes an interesting case for how metaphor can be utilised in the animated film. The fear of personal failure is an abstract phenomenon that does not have a visible equivalent, which is possible to capture on a film camera, and for this reason, Landreth must depict the experience in other means. In the combination of the audio track containing Landreth's voiceover describing his experience, and the imagery depicting the phenomena, the representation of Landreth's subjective experience of 'personal failure' is communicating the subject matter of the animation in the form of a multimodal metaphor. In this example the voiceover defines the target domain 'dread of personal failure' and visual imagery defines the source domain 'multi-coloured strings'. It is however not necessarily obvious how the source domain is mapped onto the target domain in a traditional sense, as the formalisation 'dread of personal failure is coloured strings' does not resonate well with a common metaphorical understanding.

The case of detecting a possible metaphorical interpretation of the visualisation is more difficult as Landreth in his animation has not chosen to make use of an already well-known linguistic metaphor in the soundtrack that is then animated in the imagery, which was the case in the example from Signe Baumane's ROCKS IN MY POCKET. Instead, Landreth has constructed a multimodal metaphor whereby the cue from the audio together with the imagery has deliberately been used to bring forth significant meaning and thus invited possible metaphorical interpretation. The tension that is created between what is heard in the soundtrack and the images displayed in the case of RYAN at some level works as metaphorical communication because one is made aware that the emphasis of this incident carries a meaning that goes beyond the level of pure audio-visual effects.

Briefly touching on Paul Wells and Bill Nichols' work regarding the historical predisposition towards formal and perceptual reflexivity in animation and re-enacted documentaries, animation scholar Steve Fore points out that the heightened reflexive nature of animation can strengthen the viewer's awareness of the construction of ambiguity (cf. Fore 2011). He emphasises in relation to RYAN that the "(…) viewer literally can’t believe what they see: the physical manifestations of the characters are bluntly impossible, not of our world." (Fore 2011: 288).

In the beginning of the animated short film, animator Chris Landreth establishes the premise for the fantasmatic world and the way it functions; experienced emotions and events are rendered in physical representations in the hyper-realistic environment. This is exemplified by showing a distinct visible contrast in the design between the complete computer-generated version of Landreth (Fig. 4) and the non-complete version of Landreth who has a big scar across his face and a crater in his skull (Fig. 5), furthermore aided by Landreth's elaboration of how he got those deformations while looking into and through the mirror. The awareness that arises from the use of the reflexive nature of animation enables the narrative strategy used to facilitate this set-up described as 'penetration', which Paul Wells characterises as "a revelatory tool, used to reveal conditions or principles which are hidden or beyond the comprehension of the viewer" (Wells 1998: 122).

The narrative strategy allows Landreth to show the depths of the character’s subjective mental state and experience as he perceives the events, project his thoughts onto Larkin's character and how the surrounding environment reflects his emotional state. The potential metaphorical meaning of the abstract and subjective experience of 'dread of personal failure' in RYAN is thus achieved, not by reiterating a linguistic metaphor with clearly defined target and source domains, but by creating a metaphorical relation between the audio track (target domain) and the imagery (source domain). The visual presentation of multi-coloured strings themselves, as the main character's feelings of personal failure, do not provide the metaphorical relation as this is hard to understand in the A-is-B format. Instead it could occur from the way the strings are animated and accompaniment by sound. They are only able to carry metaphorical meaning due to the noticeable difference between the 'objective (simulated) camera' and the subjective self-reflection in the mirror. To put it in Fore's words: "a tension is created between the immediacy and apparent authenticity of the soundtrack and the distinctively, vividly grotesque animated analogues of the characters as they ‘speak’ their lines." (Fore 2011: 282).

The viewer does not see a direct depiction of 'personal failure', as it is an intangible phenomenon with no visual equivalent in our world, but access is alternatively gained through Landreth's subjective experience of the phenomena, by means of establishing a highly sophisticated construction of ambiguity regarding the visuals laid in front of the viewer. The way the coloured strings are aesthetically rendered, animated and accompaniment by sound have a strong connotation of 'rope-ness' within the depicted source domain. The underlying conceptual master metaphor DIFFICULTY IS DIFFICULTY IN MOVING (cf. Lakoff 1994) aids to conceptualise the meaning of the depiction of being physically tied down to having internal struggles, and the conceptual metaphor is thus constructed to turn the animated imagery into the conceptual meaning: DREAD OF PERSONAL FAILURE IS BEING TRAPPED AND CONSTRAINED BY FANTASMATIC ROPES (Fig. 6–8).

Charles Forceville's notion regarding the aspect of time in the construction of metaphor in audio-visual images plays another important role in the making of metaphorical meaning that Landreth establishes in his animated film. Different to audio-visual content with clearly defined purposes, such as television commercials, that has been the centre of his research, Forceville stresses that metaphors in an artistic film to a larger extent may accommodate an increase in the potential mappings from the source domain to the target domain. The mapping and construction of the metaphor could happen throughout the time of the film, and this feature of developed mapping can be used to qualify and specify the potential metaphor. Having this in mind, it is my goal to furthermore describe how the metaphor 'dread of personal failure' develops from the level of multimodal mapping onto advanced metaphorical meaning-making in the animated film. In addition to forming an audio-visual relation between the source domain 'dread of personal failure' and the target domain 'multi-coloured strings' through the narrative strategy of penetration, the metaphor also conveys a more profound aspect of how Landreth conceptualises the multi-coloured strings as Larkins creative deterioration as a result of his drug and alcohol abuse. The reappearance of the metaphor, instead of explicitly mentioning the word 'alcohol' in the presentation of 'dread of personal failure', allows the viewer to interpret the implied resemblance between the animated multi-coloured strings and the dysfunction of drug abuse, in order to get a full comprehension of the animated film's subject matter in a way that does not vulgarise the portrait of Larkin.

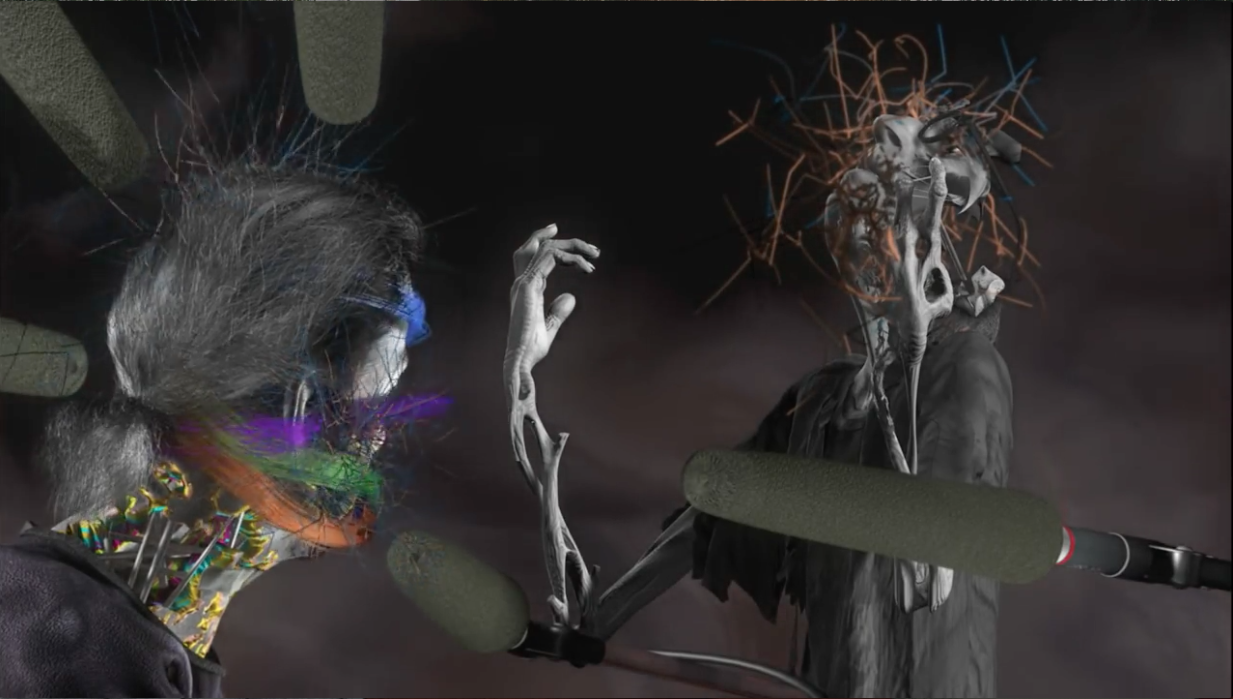

The metaphor is presented again in the animation about half way through the re-enacted interview as the conversation has moved from how Larkin had found himself to be the source of inspiration for his last hand drawn animation STREET MUSIQUE (1972). Edited bits of Larkin's animation are displayed and at the end a young version of Larkin is dancing alongside his animated figure from 1972 on the left side of the screen. He seems to be enjoying himself, and unaware of the animation ending behind him, in the audio-visual effects mimicking an old celluloid film role that is running out of filmstrip, Larkin stops in mid-motion to find himself in a totally black ambiguous space. Accompanied by the sound of a theatre lamp that is being turned on, a spotlight is lighting down on Larkin as he turns monochrome and the soundtrack becomes all silent. In a close up of his confused face, as he starts to look around, it cuts to a long and high angle shot, and thereafter an extreme long master shot showcasing that he is completely alone. Larkin is sitting with his back to the camera in a long shot with his arms wrapped around his legs, cutting to a slightly high angle long shot with Larkin now facing the camera wearing glasses and having a beard as a sign of time passing. The camera uninterruptedly zooms into a medium shot of Larkin as a bunch of pink coloured strings, similar to the one from earlier, start to appear from the top of his head as the familiar high pitch squishy sound starts. In a jump cut, that moves into a profile close-up of Larkin, the pink coloured strings move down in front of his face and tap on his glasses, before more strings appear out of his head and in the snappy motion wrap around his head in a medium shot as the image fades to white (RYAN 2004, Min. 05:52–06:23) (Clip 3).

Clip 3: RYAN (Chris Landreth, CAN 2004), Min. 5:52–6:23.

As the animated multi-coloured strings are projected onto Larkins character, in almost the exact way as with Landreth only different in how the pink-coloured string makes Larkin aware of itself, the viewer is helped to further conceptualise the metaphor, by suggesting through the audio-visual that something interrupts Larkin's creative production in an eerie manner that results in some form of isolation (Fig. 9–11). The viewer may not know exactly what the multi-coloured strings are presenting in this set-up, but as the metaphor is re-contextualised in the above scene it ties the source domain 'dread of personal failure' together with key events in Larkin's story line. The combination of audio-visual aesthetics in the scene above thus emphasises the importance of the specific metaphorical relation.

The next time the metaphor appears is when Landreth is having an interview conversation with Derek Lamb, Larkin's executive producer at the National Film Board of Canada during the late 1970's. In a medium three shot, with Lamb sitting in a big armchair in the middle and with Larkin's character frozen in time in a grey space with no floor, Lamb tells Landreth that Larkin a few years earlier had been filled with creative genius but now "(...) is living out every artist worst fear. Losing it" (RYAN 2004, Min. 06:48–06:56). The camera has in the meantime in a continued dolly pan been moving screen left, cutting into a high angle shot where bright blue strings are now visible from the top of Landreth's head. Cutting to a close-up profile shot of Lamb, Landreth is in the background seemingly distressed by the blue bunch of strings, it then jump cuts to a medium shot of Landreths, and in a slight dolly pan further multi-coloured strings begin to come out of and wrap around Landreth's head in the high pitch squishy sound, a half a second after Lamb pronounce the words 'losing it'.

Landreth struggles with the coloured strings tightening around his head as they now wrap around in snappy moves, and in a cut on action to a medium shot of the young version of Larking from the previous scene, he seems to likewise be struggling with the similar multi-coloured strings wrapped firmly around his entire head. As a pink bunch of strings comes around and grips around his head, it cuts to a extreme close-up profile shot of the young Larkin as the strings tighten so much that he in frustration puts his hands on his head before he in a high angle shot stumbles backwards to the ground fighting on his back as the strings now ties his entire body down as the camera moves away backwards into a tunnel effect with white backlight. On the audio track, Larkin can be heard in a broken up whisper mentioning cocaine and how 'I couldn't stop', and Lamb's voice continuing with " (…) and angry. His first drug addition produced some amazing work. A life can be spent really trying to get that moment back." (RYAN, Min. 06:57–07:20), and a match cut of Larkin's hand slamming onto the table at the homeless mission abruptly breaks ends the shot (Clip 4).

Clip 4: RYAN (Chris Landreth, CAN 2004), Min. 6:57–7:20.

This is the first time that the multi-coloured strings become explicitly combined with 'drugs' on the audio track, and this information is likewise an important element for the conceptualisation of the metaphor for 'dread of personal failure'. Larkin's character explains that he took cocaine and that he was not able to stop his addiction, and these words function, as described earlier in relation to Landreth's set up of his fantasmatic experience of the unfolding events, as the target domain, where the source domain of the coloured strings remains the same in aesthetic, sound and animated manner (Fig. 12–14). The metaphor has been slightly reconstructed to fit Larkin's cause of creative deterioration, and this enables the viewer to conceptually replace Landreth with Larkin's character, and vice versa. They are so to speak the same person, as the coloured strings belong to Landreth’s subjective perspective, and Larkin's description of his drug abuse triggers the same visuals as with Landreth's dread of personal failure.

The last scene where the metaphor occurs is following a discussion Landreth and Larkin have about Larkin's alcohol abuse in the cafeteria of the homeless mission. In a slightly low angle Dutch tilted close-up of Landreth's head, with root-like structures coming out and all the microphones pointing at him, he turns monochrome as his voice is heard on the audio track saying "I look at you, and I see a lot of things about my mom" (RYAN 2004, Min. 10:39–10:42). In a crash zoom into Landreth's right eye, the film cuts to an extreme close-up of an old black and white photograph of Barbara Landreth, Chris Landreth's mother, zooming out from her right eye. Dissolving from one photo to another while Barbara is progressively getting older, the photos of Barbara's face are simultaneously becoming more and more deteriorated until she in the end only consists of what looks like scarred tissue on her face with only her left eye and mouth still intact. Crash zooming into Barbara's left eye, and then in a reverse crash zoom away from Ryan Larkin's left eye, Larkin is shown in a low angle shot frozen in time with Landreth looking up towards him with his back turned against the camera. Broken whispers of Lamb and Landreth's voices repeating previous statements can be heard in the audio track, and a clearer voice-over from Landreth continues with "I see the way that she went down hill, and I see the way that you have come to this point" (RYAN, Min. 10:47–10:51).

Landreth's statement of 'personal failure' from the first scene is thereafter more clearly pronounced and repeated, as the multi-coloured strings accompanied by the high pitch squishy sound begin to wrap around Landreth's head. By a dissolve in motion into a high angle three-quarter medium shot of Landreth shown from the front, the camera pans upwards and slightly away from Landreth, as the multi-coloured strings now wrap around his complete body. Landreth is sitting in the chair tensed up and without moving, as the multi-coloured strings settle, and in another dissolve into the same image just slightly further away, Landreth hears on the soundtrack Larkin's voice loudly whispering his name "Christopher" (RYAN, Min. 11:06–11:07). Landreth turns his head screen right reacting to the voice and it then cuts into black (RYAN, Min. 10:38–11:10) (Clip 5).

Clip 5: RYAN (Chris Landreth, CAN 2004), Min. 10:38–11:10.

The camera-work used to move into Chris, Barbara and Larkin's characters, in a deliberate manner, suggests that there might be a strong connection between them. Just before the photos of Barbara, Landreth turns monochrome similar to the previous instance of the 'dread of personal failure' metaphor, and this prompts the viewer to contextualise the metaphor with consideration for the following images of Landreth's mother deteriorating from her alcohol abuse followed by Larkin's present deteriorated body caused by his alcohol addiction and end of creative production.

Larkin's current alcohol abuse triggers Landreth's dread of personal failure, as it reminds him of how his mother would drink, leaving a traumatic effect on him, and when the viewer returns to Landreth again, the multi-coloured strings start to wrap around his head in more constraining manner.

The whispers of 'personal failure' combined with the visuals of multi-coloured strings wrapping around Landreth's head, which in the first scene were used to establish the metaphorical relation between his psyche and the renderings of his subjective perspective onto the hyper-realistic environment, is in the scene above moreover visually aligned with Larkin's physical presence.

The animated multimodal metaphor 'dread of personal fear' in such recontextualization, with the added visuals of Larkin standing in front of him as a reminder of his mother's substance abuse, points to the root cause of Landreth's metaphorical relation to his psyche (dread of personal failure) and the renderings (multi-coloured strings), as Larkin's current alcohol abuse eventually turns out to be this dread of personal failure, where the multi-coloured strings 'carry over' a meaning of substance abuse.

It is at this point that the metaphorical meaning-making takes its completed form by transforming the viewers understanding of the multi-coloured strings, seen in the first scene, to present a metaphorical relation to Landreth's subjective experience of personal failure. This could lead to a finished metaphor for the 'dread of personal failure' along the lines of 'dread of personal failure is experiencing substance abuse tying down creativity'. This more elaborate metaphor is what the viewer could extract for the metaphorical meaning-making aided by the audio and imagery. The subject matter of the animated documentary film about Ryan Larkin's story from promising animator to a panhandler is in the end also a metaphorical description of the fear Chris Landreth has himself as an artist, seeing how drug addiction has destroyed his mother and Larkin.

V. Conceptual Metaphor in the Animated Film

The metaphor's target domain and source domain are impossible to state in an A-is-B construction because the analogous resemblance is not restricted to the metaphorical relation between the audial target domain 'personal failure' and the visuals of the source domain 'coloured strings', but rather in the resemblance of the target domain and the source domain lying in how Landreth’s and Larkin's characters may suffer a similar destiny. Here the multi-coloured strings in the metaphor serve to bring about this exact resemblance. The metaphorical meaning that is constructed by the audio-visuals mapped onto both character's stories of personal failures, makes it only possible to grasp the subject matter of the animated film when the viewer realises, at the end of the animation, how Landreth's 'dread of personal failure' is multi-coloured strings that consistently grasp hold of Larkin's creative abilities due to alcohol abuse. The metaphor consists of all the scenes working together to establish the metaphorical meaning-making, and only in animation can the multimodal metaphor become a literal metaphor, as Landreth's metaphor 'dread of personal failure' is not only cued from the audio track but is at the same time a literal visualisation of the metaphor (cf. Leyda [ed.] 1986: 48–49). The tension between the hyper-realistic image, indexical sound and the 'penetration' of Landreth's mental state enables an audio-visual tension, due to the medium-specific properties of the animated film, that has been used to the greatest extent, to allow for a metaphorical understanding when the animated medium re-contextualise the target and source domains into multimodal metaphors.

Chris Landreth coined the term 'psychorealism' (cf. Fore 2011, referencing Robertson 2004) to describe his method for animating internal realities as rendered manifestations in its hyperreal environment. Departing from the discussion of longstanding conventions in classical live action documentaries, Landreth exemplifies in RYAN how subjective perspective as a multimodal metaphor in the animated film influences the process of creating novel metaphorical meaning regarding subjective representations. This has made the term become closely associated with the effective ways in which metaphor in the animated film is utilised on a more advanced level. In relation to her animated documentary, AN EYEFUL OF SOUND (CAN / NL / UK 2010) about audio-visual synaesthesia Samantha Moore is discussing the use of psychorealism to represent subjective experiences. In the production of her animation she points out that "in contrast to RYAN; instead of using metaphor as a short cut to convey generally understood internal feelings, I was visualising unusual internal feelings as literally as I could and then trying to explain them with context” (Moore 2011: 4). This approach seems to assert the notion that conventional metaphors as a pragmatic tool to represent subjective experience struggle to reproduce a wider range of subjectivity, because they are committed to portraying 'generally understood feelings' that can easily be recognised and conceptualised by the viewer via an A-is-B convention that turns the abstract into something visible for the eye (concrete).

Studies into multimodal metaphors expressed in live action films lead by Professor Hermann Kappelhoff, however, suggests that metaphoric meaning to a larger extent could be concerned with making the metaphorical meaning accessible to others by activating the felt embodiment of the viewer through the expressive movements arising from the film by means of the audio-visuals over the course of time (cf. Kappelhoff /Müller 2011: 133–137). This notion opens up the metaphor to becoming a process rather than a static tool, that makes its conceptualisation arise from medium-specific abilities to create unique metaphorical relations between sound and image, and from its total experience constructs conceptual metaphoric meaning-making that is not present in the audio-visuals alone but reactivates perceptual sensation. RYAN is an example of an animation that in a similar way is utilising such highly creative means of metaphoric meaning-making to represent the subjective perspective of its character in terms of a felt experience of confinement by the multi-coloured string as the audio-visuals unfold the metaphor over time. The concepts represented in the animated short film, which aim to communicate Landreth's 'dread of personal failure', are reconstructed through our embodied and conceptual understanding that what we experience as subjects cannot only be communicated literally in one image or mode - but must be expressed metaphorically through the medium specific constellation of audio-visuals, expressive movement and our experience with the fantasmatic mode in the animated film.

VI. Conclusion

It was the aim to show how metaphors in the animated film can work in the continuum of spoken conventional metaphor onto creative multimodal metaphors to constitute metaphorical meaning. As an example of the former, the first case study of the 'she is a bright student' metaphor from the animated feature film ROCKS IN MY POCKETS, showcased how the conventional spoken metaphor INTELLIGENCE IS A LIGHT-SOURCE (cf. Sullivan 2013) can be fairly directly reiterated in the animated film's imagery, aided by the narrative strategies of animation, and in this case that of metamorphosis. Such an approach to metaphorical representation in the animated film does at best clarify and emphasise the linguistic expression, but may also risk reducing the animation to mainly supplementary accessories, as the metaphorical relation between target and source domains remain monomodal, leaving only little space for ambiguity in terms of animated presentation.

By accounting for theoretical components of animation studies such as the emergence of subjective expression in the (traditional) genre of documentary (cf. Ward 2006), the formalisation of narrative strategies in animation (Wells 1998) and the importance of time in metaphorical meaning-making in film (cf. Forceville 2007b), it becomes possible to show how the second case study of the 'dread of personal fear' metaphor in the animated documentary RYAN demonstrates the animated film's ability to represent subjective perspectives as complex creative metaphors. This can be achieved through the multimodal nature of the medium, which utilises audio-visual elements to establish metaphorical relations between target and source domains to awake a strong sense of ambiguity that engages the viewer's perceptual and embodiment conceptualisation. The development of metaphorical meaning over time stresses that the time aspect of multimodal metaphors in the animated film enables a 'carrying over' of subject matter that is bigger than its parts.

VII. Ending Notes

The exploration into creative metaphors in the animated film and how animation and metaphor interact and influence each other is not at all exhausted. Here are some few very brief suggestions for further investigation. Charles Forceville has in his research on multimodal metaphors looked at Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner’s Blending Theory (cf. Forceville 2007c). Two of his observations are of specific interest in relation to the animated film to aid an understanding of the potential of metaphorical meaning-making in this medium. The Blending Theory supports the notion that conceptual structures are often combinations of two or more inputs that 'blend' into a third emergent structure (cf. Fauconnier / Turner 2002). The animated film could base on its fantasmatic ability showcase variations of these blended structures and help the investigation into how the inputs generate conceptual meaning regarding these medium-specific features. As Metaphor Theory mainly works with only two semiotic domains, the Blending Theory could as well help to account for conceptual representations in the animated film that Metaphor theory might struggle with, as this model allows for more than two inputs, and the animated film could, therefore, benefit from examining the different conceptual domains it draws from to represent metaphorical meaning-making.

Prof. Hermann Kappelhoff's theory on cinematic expressive movement is concerned with the audio-visual aesthetics to form the grounds for constructing multimodal metaphorical meaning-making over the course of time, by exposing underlying patterns that activate felt embodied experiences and concepts via e.g. elements of cinematography, gesture, music (Kappelhoff and Müller 2011). Adopting such an approach to conceptual meaning-making could furthermore provide an insight into how the animated film may utilise similar felt embodied experiences, rather than purely conceptual awareness, arising from expressive movements. Finally, Gerard Steen’s Deliberate Metaphor Theory, which "(…) involves people using metaphor as metaphor: it makes intentional use of one thing to think about something else" (Steen 2013: 181), could additionally help explore medium specific means the animated film utilises to captivates the viewer’s attention with audio-visual representations of semantic domains. Such awareness might support a better understanding of when the animated film intentionally, or unintentionally, communicates potential conceptual metaphorical meaning different to metaphors that may be understood more literally, and how animated film can be directed to make the metaphorical thinking conscious.

It is clear that it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss all aspects of the relevant research produced in the area of multimodal metaphor in the moving image. However, it is the hope to set in motion a discussion on how metaphor in the animated film is facilitated, as both practitioners and scholars seem to claim that 'metaphor' is a film devise widely used in this medium. Due to the sparse literature in the field of animation, and with a dominant focus on live action in film studies, the point of these case studies was to articulate that if metaphors in the animated film were simply visualisations of conceptual metaphors, one might not expect to see vivid audio-visual representations, such as in RYAN. Considering that animation theory and metaphor research is more elaborate than reducing meaning-making to strictly conceptualised linguistic metaphors that enable an "understanding one thing in terms of another" (Lakoff / Johnson 1980: 5), it could indicate that the medium of animation has more to offer in regards to our understanding of how metaphorical meaning-making functions. The question of whether something is or is not metaphorical in the animated film must thus rely on how this is established as metaphorical, and the goal of these studies was to provide an insight into the ways the animated film provide an opportunity for metaphorical qualification and interpretation with a specific focus on subjective perspective as creative metaphors.

Literature

Cavallaro, D.: Art in Anime. The Creative Quest as Theme and Metaphor. Jefferson 2012.

Crafton, D.: The Veiled Genealogies of Animation and Cinema. Animation. An Interdisciplinary Journal 6/2 (2011), 93–110.

Bolognesi, M.: VisMet 1.0 (2014). In: http://www.vismet.org/VisMet/index.php (accessed 31 January 2017).

Fauconnier, G. / Turner, M.: The Way We Think. Conceptual Blending And The Mind's Hidden Complexities. New York 2002

Firth, D. / Michalkow, Steven A.: Mining the Dreamscape. An Interview with David Firth. Former People (28 February 2014). In: https://formerpeople.wordpress.com/2014/02/28/mining-the-dreamscape-an-interview-with-david-firth/ (accessed 31 January 2017).

Forceville, C.: Pictorial Metaphor in Advertising. London 1996.

Forceville, C.: Metaphor in pictures and multimodal representations. In: Raymond Gibbs (ed.): The Cambridge Handbook of Metaphor and Thought. Cambridge 2008, 462–482.

Forceville, C.: From Pictorial to Multimodal Metaphor (Lecture 3 of 8). In: ibid.: Course in Pictorial and Multimodal Metaphor (2002–2013, here 2007a). In: http://semioticon.com/sio/courses/pictorial-multimodal-metaphor/ (accessed 31 January 2017).

Forceville, C.: Pictorial and multimodal metaphor in fiction film (Lecture 5 of 8). In: ibid.: Course in Pictorial and Multimodal Metaphor (2002–2013, here 2007b). In: http://semioticon.com/sio/courses/pictorial-multimodal-metaphor/ (accessed 31 January 2017).

Forceville, C.: Metaphor, Hybrids, and Blending Theory (Lecture 6 of 8). In: ibid: Course in Pictorial and Multimodal Metaphor (2002–2013, here 2007c). In: http://semioticon.com/sio/courses/pictorial-multimodal-metaphor/ (accessed 31 January 2017).

Forceville, C.: The Flesh and Blood of Embodied Understanding. The Source-Path-Goal Schema in Animation Film. Pragmatics & Cognition 19/1 (2011), 37–59.

Forceville, C. / Urios-Aparisi, E. (eds.): Multimodal Metaphor. Berlin / Boston 2009.

Fore, S.: Reenacting Ryan. The Fantasmatic and the Animated Documentary. Animation. An Interdisciplinary Journal 6/3 (2011), 277–292.

Honess Roe, A.: Animated Documentary. London 2013.

Kappelhoff, H. / Müller, C.: Multimodal Metaphor and Expressive Movement in Speech, Gesture, and Feature Film. Metaphor and the Social World 1/2 (2011), 121–153.

Kuhn, A. & Westwell, G.: A Dictionary of Film Studies. Oxford 2012.

Lakoff, G. / Johnson, M.: Metaphors We Live By. Chicago 1980.

Lakoff, G.: Conceptual Metaphor Home Page. Berkeley 1994. In: http://www.lang.osakau.ac.jp/~sugimoto/MasterMetaphorList/MetaphorHome.html (accessed 31 January 2017).

Leyda, J. (ed.): Eisenstein on Disney. Calcutta 1986.

Lucander, Åsa / Cowley, Laura-Beth: Interview with ‘Lost Property’ Director Åsa Lucander and Animator Marc Moynihan. Skwigly Online Animation Magazine (26 August 2014). In: http://www.skwigly.co.uk/lost-property/ (accessed 31 January 2017).

Moore, S.: Animating Unique Brain States. Animation Studies Online Journal 6 (2011). In: https://journal.animationstudies.org/samantha-moore-animating-unique-brain-states/ (accessed 27 October 2016).

Nichols, B.: Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington 2001.

Pilling, J. (ed.): A Reader in Animation Studies. Bloomington 1997.

Pilling, J. (ed.): Animating the Unconscious. Desire, Sexuality, and Animation. New York 2012.

Prince, S.: True Lies. Perceptual Realism, Digital Images, and Film Theory. Film Quarterly 49/3 (1996), 27–37.

Reckart, T. / Sarto, D.: Tim Reckart Talks 'Head Over Heels'. Animation World Magazine (8 February 2013). In: http://www.awn.com/animationworld/tim-reckart-talks-head-over-heels (accessed 31 January 2017).

Robertson, B.: Psychorealism. Computer Graphics World 27/7 (2004). In: http://www.cgw.com/Publications/CGW/2004/Volume-27-Issue-7-July-2004-/Psychorealism.aspx (accessed 28 January 2017).

Rozenkrantz, J.: Colourful Claims. Towards a Theory of Animated Documentary. Film International (2011). In: http://filmint.nu/?p=1809 accessed 21 November 2016.

Steen, G.: Deliberate Metaphor Affords Conscious Metaphorical Cognition. Journal of Cognitive Semantics 5/1–2 (2013), 179–197.

Steen, G.: Developing, Testing and Interpreting Deliberate Metaphor. Journal of Pragmatics – An Interdisciplinary Journal of Language Studies 90 (2015), 67–72.

Sullivan, K.: Frames and Constructions in Metaphoric Language. Amsterdam 2013.

Svankmajer, J. / Jackson, W.: (1997, June): The Surrealist Conspirator. An Interview With Jan Svankmajer. Animation World Magazine (6 June 1997). In: http://www.awn.com/mag/issue2.3/issue2.3pages/2.3jacksonsvankmajer.html (accessed 31 January 2017).

Swift, S.: What is a Symbol? What is a Metaphor? Coleridge, Wordsworth, Keats. YouTube (2015). In: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TrrsNqJKJBg (accessed 27 October 2016).

Tan, S. / Darmono, L.: The Lost Thing. Interview With Shaun Tan. Motionographer (19 January 2011). In: http://motionographer.com/2011/01/19/the-lost-thing-interview-with-shaun-tan/ (accessed 31 January 2017).

Vázquez, A. / Rivero, P.: Psiconautas, The Forgotten Children. European Animated Feature Film (4 December 2016). In: http://www.europeanfilmawards.eu/en_EN/interview-on-animated-feature-filmpsiconautas (accessed 31 January 2017).

Ward, P.: Documentary. The Margins of Reality. New York 2006.

Wells, P.: Understanding Animation. London 1998.

Wells, P.: Animation. Genre and Authorship. London 2002.

Wu, W.: In Memory of Meishu Film. Catachresis and Metaphor in Theorizing Chinese Animation. An Interdisciplinary Journal 4/1 (2009), 31–54.

Filmography

AN EYEFUL OF SOUND. Samantha Moore. UK 2010.

ROCKS IN MY POCKETS. Signe Baumane. USA 2014.

Via Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/ondemand/rocksinmypockets (last accessed 31 January 2017).

RYAN. Chris Landreth. CA 2004.

Via: https://www.nfb.ca/film/ryan/ (last accessed 24 January 2017).

STREET MUSIQUE. Chris Larkin. CA 1972.

Via: https://www.nfb.ca/film/street_musique_en/ (last accessed 24 January 2017).